Corbusean vocabulary

Brutalism

An architectural movement characteristic of the Modern Movement that emerged after World War II. It is mainly characterized by the use of raw concrete, or materials left untreated. From the 1950s onwards, Le Corbusier’s work reflected the characteristics of Brutalism, notably in his desire to leave materials unfinished or with the marks of the formwork removed. Examples include the Usine de Saint-Dié, the Unités d’Habitation, the Maisons Jaoul and the Tour d’ombres.

Five points for a new architecture

Although theorized in 1927, the five points first appeared in 1923 when the Maison La Roche was built.

Pilotis allow for an open floor plan and free circulation under the building.

The long horizontal window inserts uninterruptedly into the façades, which are non-load-bearing envelope elements.

The roof-garden replaces the traditional attic, offering a suspended garden at the top of the house.

The open floor plan offers total freedom for the interior layout and makes the distribution of each level independent.

The open façade forms an envelope independent of the structure.

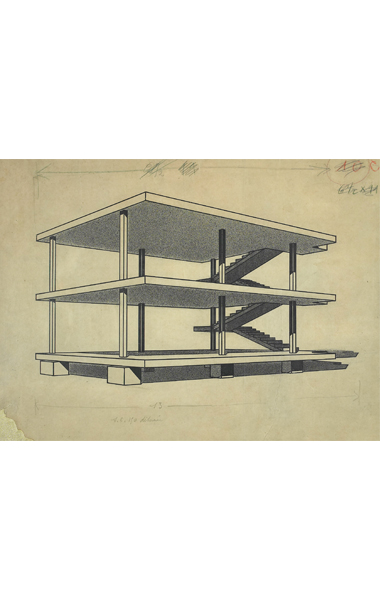

Dom-ino

A contraction of the words Domus (Latin for house) and innovation, the Dom-Ino system is a modular construction process developed by Le Corbusier in 1914. It is a post-and-beam principle, consisting of three slabs, six posts and a staircase, with each module combinable. This procedure makes it possible to implement the five points for a new architecture, but above all to standardize serial construction. Le Corbusier used this system throughout his career, from the Villa Schwob to the Unités d’Habitation and the Villa Savoye.

Machine for living

« The house has two purposes. First of all, it’s a machine for living, that is to say, a machine designed to provide us with an efficient aid for speed and accuracy in work, a diligent and considerate machine to satisfy the body’s demands: comfort. But then it is the useful place for meditation, and finally the place where beauty exists and brings the mind the calm it needs; I am not claiming that art is swill for everyone, I am simply saying that, for certain minds, the home must bring the feeling of beauty. »

Le Corbusier, Almanach d’architecture moderne, Paris, Crès, 1925, p. 29

Open Hand

The Open Hand is a symbolic motif in Le Corbusier’s plastic and architectural work. It was not until the early 1950s that Le Corbusier materialized the form, even though the unrealized project for the Monument pour Paul Vaillant-Couturier in 1938 included an imposing hand sculpture.

Although it appears mainly in sketches, colored or not, through a production of drawings, lithographs (notably in Poème de l’Angle droit in 1953), paintings and pasted paper, it is embodied above all in two architectural projections, one in Chandigarh and the other in Ahmedabad, with the Bakhra dam. This recurring motif takes on its fraternal and universal dimension through its motto: “Pleine main j’ai reçu, Pleine main je donne” (“Full hand I received, Full hand I give”).

The only version built dates back to 1986, at the Capitol Complex in Chandigarh, between the Assembly Palace and the High Court.

« Open to receive. Open, too, for everyone to take. Water trickles down, the sun illuminates, complexities have woven their threads, fluids are everywhere. Tools in the hand. The caresses of the hand. Life tasted through the kneading of hands. The sight that lies in palpation.

Full hand I received full hand I give »

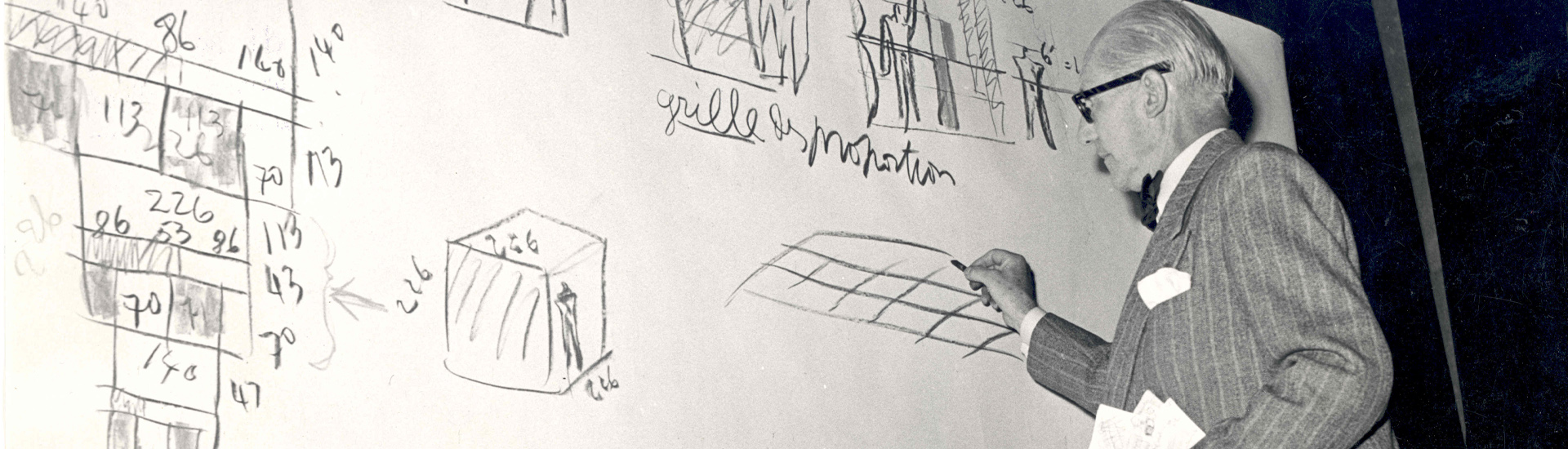

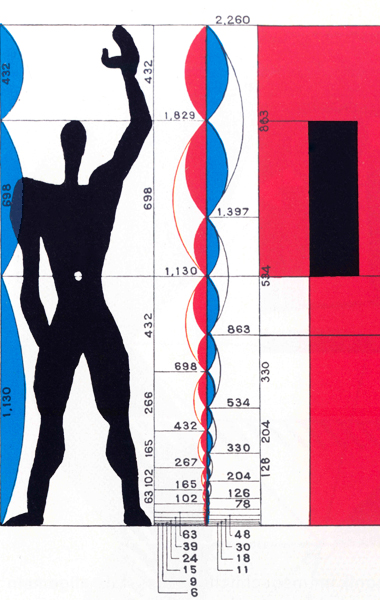

Modulor

The Modulor is a system of anthropometric proportions and a tool for architectural design and construction standardization.

Although Le Corbusier began research into numbers as early as 1904, he developed the Modulor between 1943 and 1950, with the help of his workshop (mainly Gerald Hanning). After being designed for a stature of 1.75 m (Le Corbusier’s own height), it was finally based on a man’s height of 1.83 m or 6 feet, inspired by the Fibonacci sequence and the golden section, which is supposed to divide the body harmoniously. Both an architectural fantasy and a practical measure, the Modulor condenses Le Corbusier’s interest in proportions, natural structures, the human scale and the industrialization of architecture. It was disseminated mainly through two publications (Le Modulor, 1950 and Modulor 2, 1955) and was applied in almost all of Le Corbusier’s post-war projects on the rue des Sèvres (Unité de Marseille, Usine de Saint-Dié…).

Objects of Poetic Reaction

For Le Corbusier, objects with a poetic reaction are raw, natural materials or manufactured objects from which he draws his artistic inspiration. From a pine cone to a crab shell, from a pebble to a seashell, Le Corbusier collected hundreds of objects throughout his life. These objects can be found in many of his creations, from the bas-reliefs inlaid in concrete to the motifs in Poème de l’angle droit, as well as in his drawings and paintings.

Architectural promenade

The idea of the “architectural promenade” first took shape in 1923, with the construction of the Maison La Roche, although the term didn’t appear until 1929, in the first volume of the Œuvre complète. For Le Corbusier, interior circulation was a preoccupation that he would develop throughout his career: “Everything, including architecture, is a question of circulation”.

The principle of the “architectural promenade” comprises three essential elements: firstly, the use of various architectural means to create an entrance that awakens the viewer’s curiosity and compels him or her to go beyond; secondly, the production of varied and multiple viewpoints; and thirdly, the maintenance of the relationship between fragments and architectural unity.

« Arab architecture has a precious lesson for us. You appreciate it on foot, walking. Only on foot, in movement, can you see the developing articulation of the architecture. It's the opposite principle to that of Baroque architecture, which is conceived on paper, from a theoretical standpoint. I prefer the lesson of Arab architecture »

Purisme

« Purisme strives for an art free of conventions which will utilize plastic constants and address itself above all to the universal properties of the sens and the mind ».

Amédée Ozenfant and Le Corbusier, « Le Purisme», in L’esprit Nouveau, janvier 1921

Purism is an aesthetic doctrine born of criticism of Cubism, formulated by Amédée Ozenfant and Le Corbusier, which they considered too decorative: “A painting is the association of purified, associated, architectural elements”. The pictorial theory of purism was extended to Le Corbusier’s architecture: the La Roche and Jeanneret houses were its first expression.

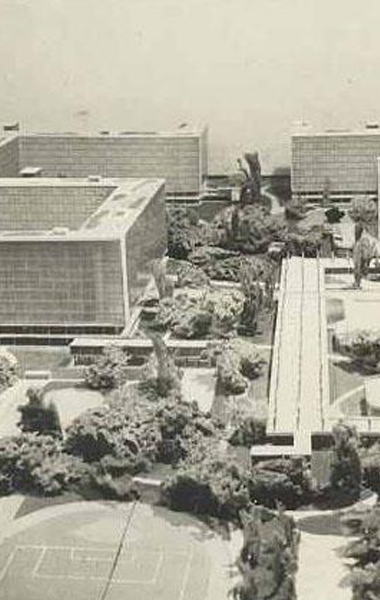

Radiant City

For Le Corbusier, the Radiant City is intended to shelter people “from a society that has become machine-driven”, and should be placed “under the masterly aegis of the conditions of nature: sun – space – greenery, and the mission being dedicated to the service of man: TO DWELL – TO WORK – TO CULTIVATE THE BODY AND THE MIND – TO CIRCULATE (in this order and hierarchy)”. (Le Corbusier, preface to the reprint of La Ville Radieuse, 1964).

For Le Corbusier, urban planning can only be conceived architecturally, and must necessarily include the sky and trees, so that inhabitants can access “essential joys”.

Le Corbusier took up the main theoretical principles of the Radiant City in a book of the same name published in 1935.