Unité d'Habitation

Berlin, Germany, 1955-1958

« Now that the HOUSING UNIT is in the process of being erected at the Heilsberger Dreieck, I call on German opinion to witness the arbitrary distortion of my plans. These plans were the product of tireless study and careful consideration: a labour of constant trial and error going back to 1907, in other words the work of fifty years. It is all this that has produced the HOUSING UNIT. […] And now in Berlin, in the face of the authorities and their loyal support, by what right can the work of a guest be thus dramatically disfigured, the work of a man invited and honoured with a special commission? »

Commission

At the end of the Second World War, Germany was a country largely in ruins and the authorities had to face a dramatic demand for new housing. Work was begun nearly ten years after that in France and, in West Berlin alone, no fewer than 500,000 homes needed to be rebuilt.

On the pattern of other international exhibitions dealing with problems of town planning and housing, Germany launched its Interbau, an International Building Exhibition (IBA ’57) dealing with construction, architecture and experimental techniques – although the exhibition itself was not held until 1957. In February 1955, working closely with the Association of German Architects and the Federal Ministry of Construction, the West Berlin Senate had invited Le Corbusier – together with Alvaar Aalto, Walter Gropius, Oscar Niemeyer and others – to take part in the exhibition and to submit a project for the competition organized on this occasion. This was the second time, almost thirty years after the Weissenhof-Siedlung Houses in Stuttgart, that Le Corbusier had been invited to build in Germany.

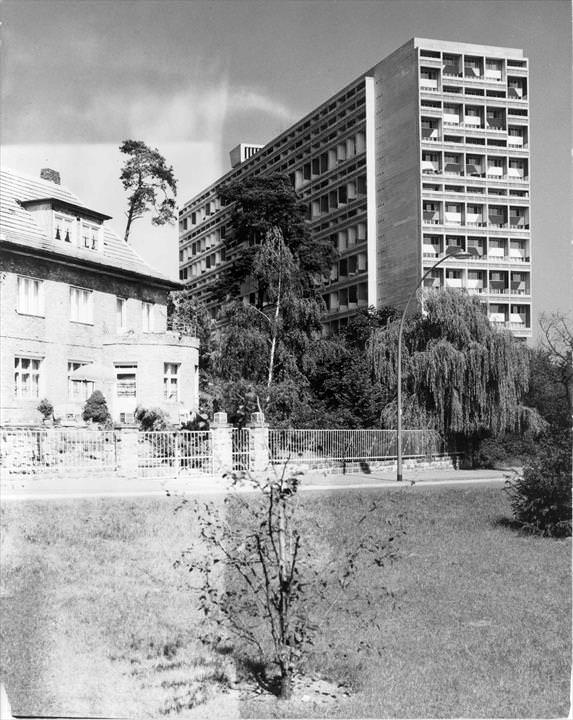

Le Corbusier was the only architect allowed to choose his own site. This was because the planned site, in the Hansa district, was not large enough for the proposed Housing Unit. It was replaced by a site in Charlottenburg, a district to the west of the city. The 10 acre plot, located on a hill, was close to the Olympic stadium built for the 1936 games.

Project

The initial plans, broadly reproducing the characteristics of the Cité Radieuse in Marseille, were sketched at the Atelier at 35 rue de Sèvres in March 1956. As in Marseille, the Berlin Housing Unit was to be equipped with “shopping streets” and services (dropboxes for medical prescriptions, a daycare centre, a school). This preliminary project also provided for underground parking.

In July 1956, the Baupolizei (building regulations authority) imposed restrictive building standards, raising the minimum ceiling height to 2.50 m, when Le Corbusier’s Modulor scale of measurement specified a height of 2.26 m. This was the first of many disruptions of Le Corbusier’s project. The many changes included removal of the emergency outside staircase, of the two-floor apartments, the facilities (shops and services) the car park and especially the roof terrace (no facilities, no access). Despite Le Corbusier’s repeated objections, these important features were not included in the final programme.

Structural work began in January 1957 and the site was completed eleven months later. It was exemplary in many respects: rigorous technical studies, work completed in record time, prefabrication in the factory and on site, etc. The result is a Housing Unit in raw concrete, made up of 557 dwellings culminating at a height of 53 m for a width of 23 m and a length of 141 m. The polychromy of the facades is different from that of the other Units, it obeys a system of superimposed colour duos on the walls separating the loggias (yellow/red, purple/white, dark green/white), and another system of pairs of colours separated by an oblique (black/blue, red/white…).

The apartments are served by interior “streets”, ten in number and accessed by two lifts. Each landing is equipped with a bicycle storage area. The Unit has 173 one-room apartments, 267 two-room duplexes, 85 three-room duplexes, 4 four-room apartments and 1 five-room duplex, all with a loggia. The occupants also have the use of the communal areas: the entrance hall, the post office, the shops on the ground floor and the laundromat.

Being himself unable to see to furnishing details or to delegate them to a collaborator in the rue de Sèvres, Le Corbusier authorized Ingrid Dlugos, an interior designer in Berlin, to furnish several apartments for the exhibition.

Subsequent History

Today the Berlin Housing Unit is still occupied and, since 1979, it has functioned as a residential co-ownership entity. It sets up scientific and cultural events organized by the Corbusierhaus Berlin Association, founded in 2004.

Restoration carried out in 1974 made it possible to limit material deterioration of the facades but altered the “raw” aspect of the concrete. Several other measures followed in 1984 and 1986.

The entrance hall, the inner streets and the facades were accorded historical monument protection measures in 1994.