Unité d'habitation

Marseille, France, 1945-1952

« The origin of this research […] goes back to my visit to the Charterhouse of Ema near Florence, in 1907. I saw, in this musical landscape of Tuscany, a modern city crowning the hill […] each cell has a view of the plain, and opens onto a small, completely enclosed garden below.

I thought I would never be able to come across such a cheerful interpretation of the habitation [...] This "modern city" dates from the fifteenth century. The radiant vision stayed with me forever. »

Commission

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the government’s priority was rehousing, reconstruction and finally redevelopment of the territory. In Marseille destruction was widespread: the ruins extended over close to 25 acres; some 3,600 buildings had been destroyed and 10,800 partially damaged.

On July 20, 1945, the Minister of Reconstruction and Urbanism Raoul Dautry commissioned Le Corbusier to construct a collective building. Passing from the Maison Dom-ino to the Radiant City, via the Villa apartments and the City of Three Million Inhabitants, Le Corbusier presented Marseille with the high point of more than twenty years of research on housing, the links between the individual and the collective, but also the place of nature in architecture and urban planning. His reflection is not solitary: between the CIAM (International Congress of Modern Architecture) and the creation of ASCORAL (Association of Builders for Architectural Renovation) in 1943, Le Corbusier continued to reflect, together with his colleagues, on architecture and the city.

After several proposals, the final version of the Marseille Housing Unit was adopted in March 1947. The land chosen was located in the middle-class neighbourhoods in the south of Marseille, between the hill and the sea. The Marseille Housing Unit was designed by Le Corbusier and his workshop directed by André Wogenscky, together with the Atelier des Bâtisseurs (ATBAT) founded by Le Corbusier and with its management entrusted to Vladimir Bodiansty.

Project

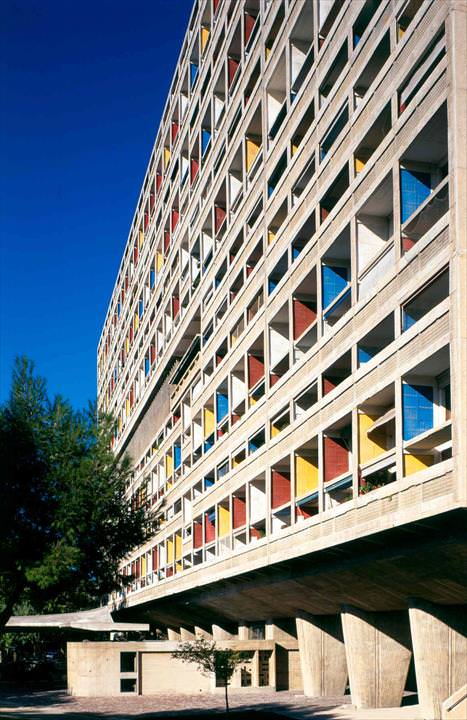

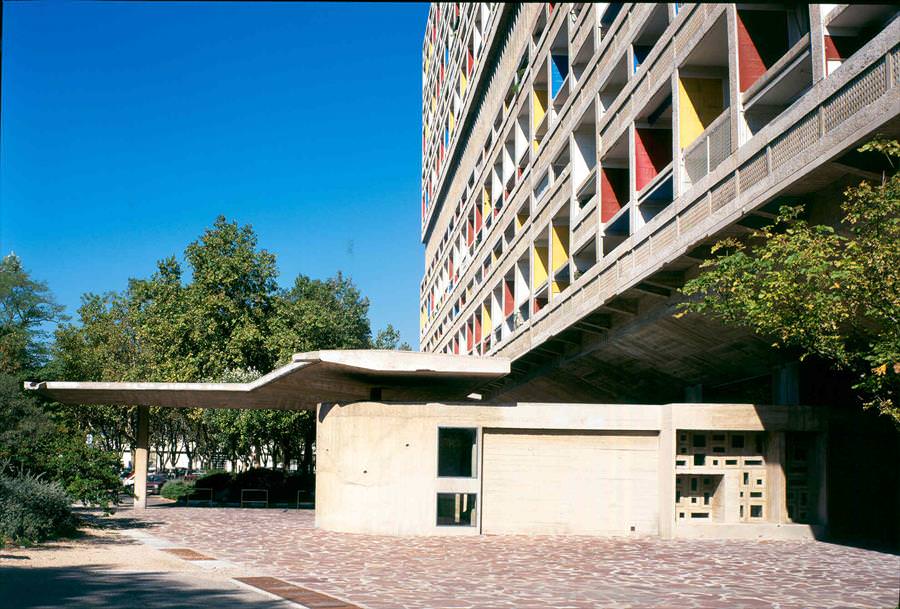

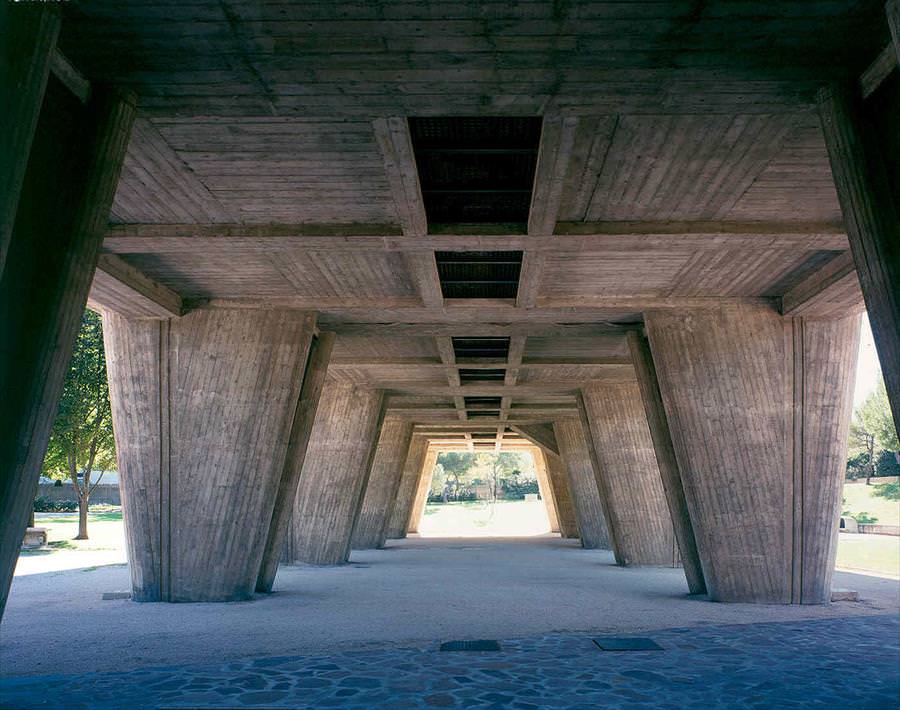

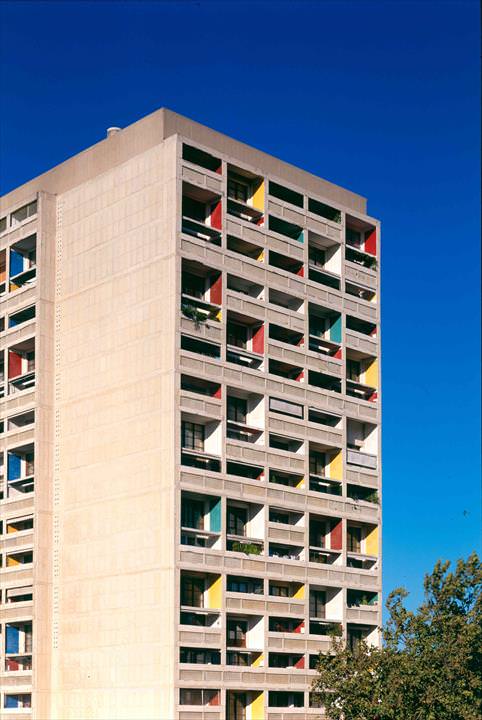

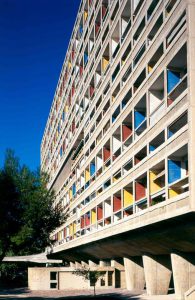

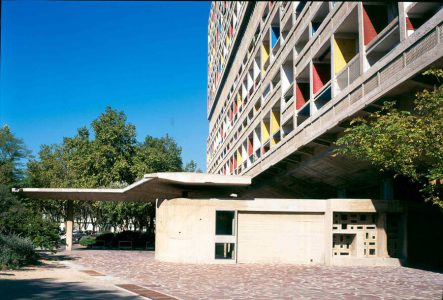

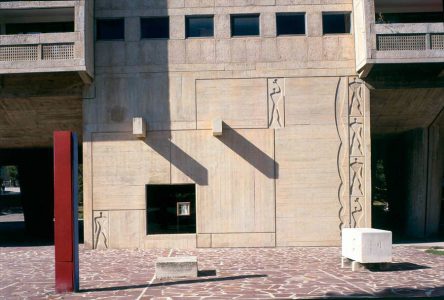

Simultaneously an architectural experiment, an urban concept and a social experience, the Marseille Housing Unit brings together 330 housing units with modern comfort as well as collective spaces. The building is 135 m long, 24 m wide, 56 m high. The Unit is mounted on stilts in order to save space on the ground both for greenery and to allow pedestrians and cars to circulate beneath it. The use of pilotis is an essential element of the Green City designed by Le Corbusier. The building is moreover located in the centre of a wooded park.

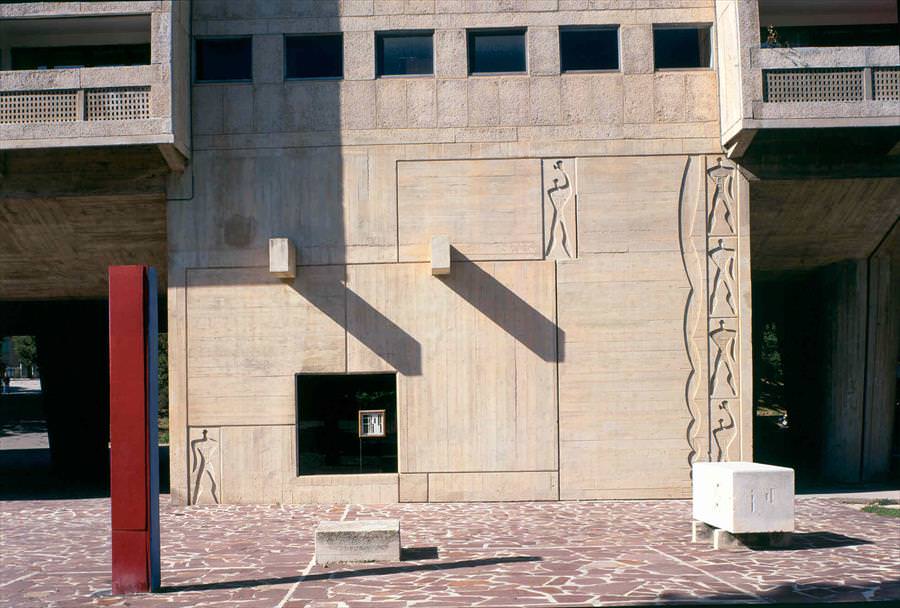

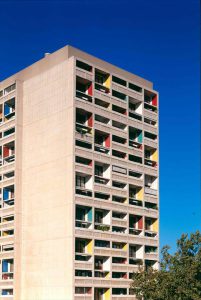

The Housing Unit is made according to Modulor and its frame is in reinforced concrete cased in situ. The facades are sometimes raw, sometimes painted, as at the level of the loggias. The apartments are accessible from the large entrance hall giving access to the lifts and the staircases.

The apartments are divided into 23 different types, assembled on the “bottle rack” principle, i.e. they are built in an independent framework of reinforced concrete posts and beams. They rest on a primary structure called “artificial ground,” a network of transverse and longitudinal beams.

These 23 types are designed using eight combinations made possible by the use of three standard modules. The first module brings together the entrance, the hallway, the kitchen and the living room; the second is occupied by the master bedroom and the toilet block while the third module is intended for two children’s bedrooms.

Although their sizes vary (from a single person’s home to an apartment for a family with eight children), their organization is similar. The apartments, with the exception of those on the south facade, are through. They may be on two floors connected by a staircase. These were made in collaboration between Jean Prouvé, the workshops of Nancy and Le Corbusier. Their design is standardized, made up of different independent cells. There is no contact between the different apartments and they are soundproofed in order to guarantee the privacy of each family. Deeply impressed by his visit to the Ema Charterhouse in 1907, Le Corbusier wanted each dwelling to remain independent within the unit.

The accommodations are all equipped with modern comfort: running water, central heating, sanitary facilities and a ventilation system. The kitchen units, designed by Le Corbusier and ATBAT, together with Simone Galepin and based on a proposal by Charlotte Perriand, are equipped like laboratories (electric cooker, rubbish chute, refrigerator cabinets, multiple storage units).

The apartments all benefit from a loggia in the living room with double-glazed bay windows that fully let in the light in winter, while brise soleils are designed to filter it out in summer.

The apartments are accessed by a system of interior streets, which not only allow the occupants accede to their apartments, but also allow mail and purchases from the Housing Unit’s grocery store to be delivered. Le Corbusier saw the Unité d’Habitation as a “vertical city,” with shopping streets on the 7th and 8th floors. Thus there are various shops within the building and there is even a hotel-restaurant for the use of occupants’ families.

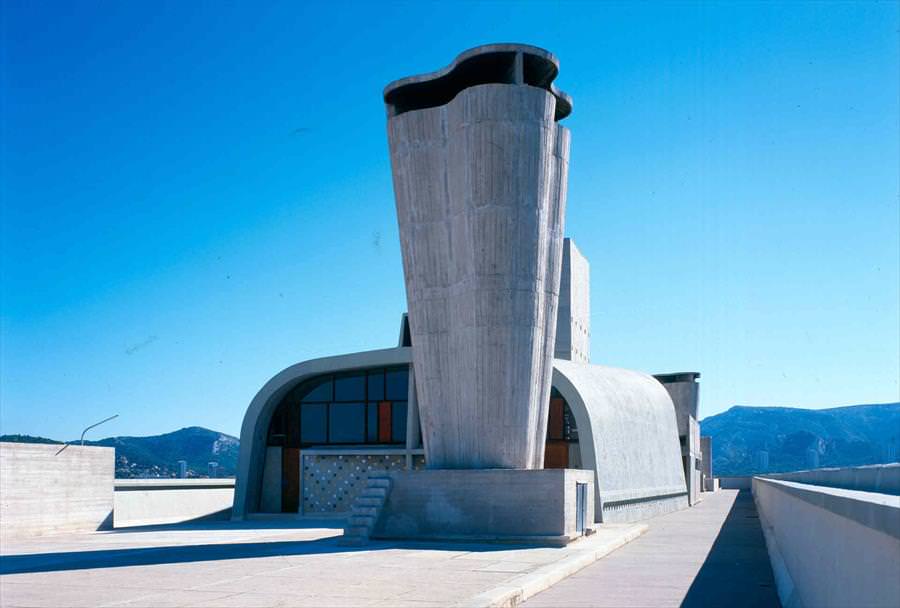

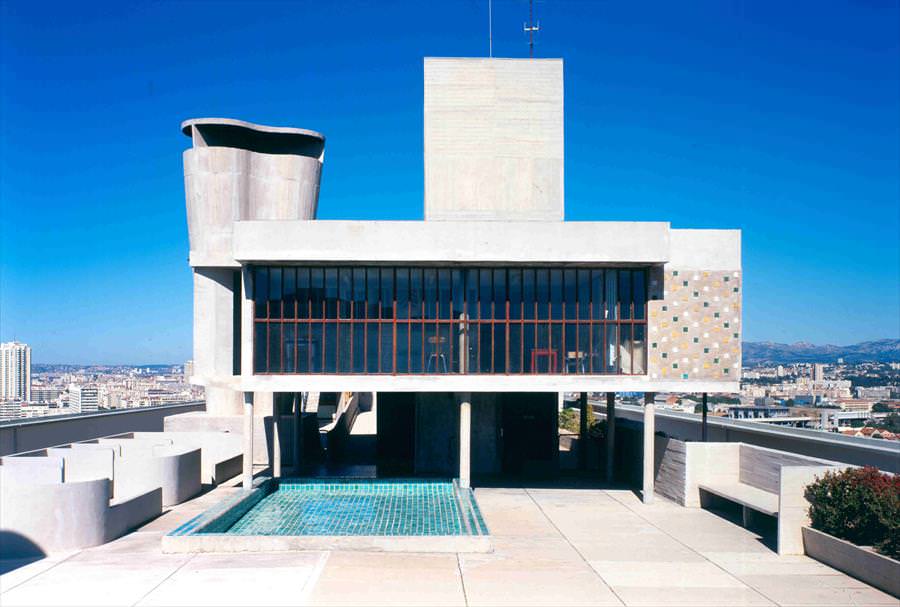

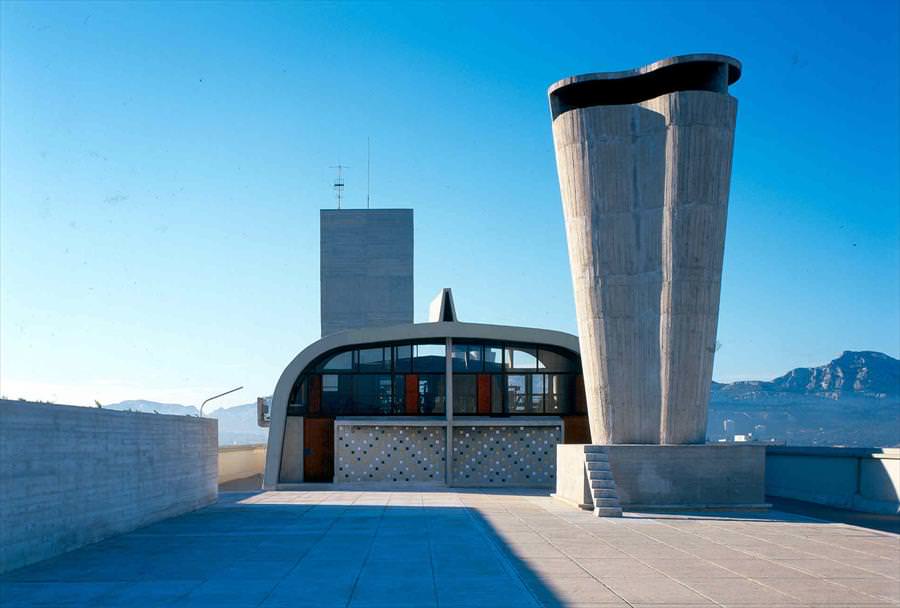

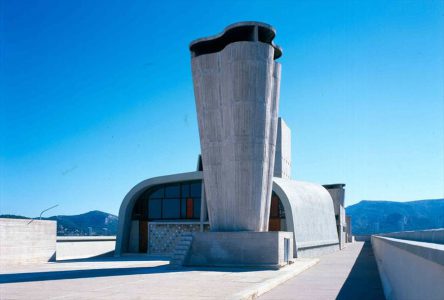

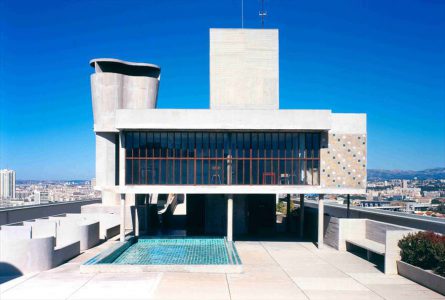

Full use is also made of the Housing Unit’s roof. The 300 sq m roof terrace includes a running track, a gymnasium, an open-air theatre, a nursery school with a paddling pool, and above these a day nursery, now a paint shop.

The garden is lit by luminous concrete bollards. There is also the “Measurement Stele” and a refuse collection station. The Marseille Housing Unit was inaugurated on October 14, 1952.

On that occasion, Eugène Claudius-Petit, then Minister of Reconstruction and Urban Planning, presented Le Corbusier with the insignia of Commander of the Légion d’Honneur.

Subsequent History

Rapidly becoming a symbol of modern architecture and a founding work of Brutalism, the Cité Radieuse in Marseille is a remarkable example of the balance between individual housing and collective living; today it is still occupied as an apartment block. It influenced many later projects, being the first Housing Unit to be built. Rezé-les-Nantes, Berlin, Briey en Forêt and Firminy were to follow.

Since 2013, the gymnasium of the Marseille Housing Unit has housed the Mamo (Marseille Modulor), a contemporary art centre by the designer Ora Ito. The Level One street still includes a bookshop specializing in architecture, a hotel, a restaurant, an art gallery and a mini-market, etc. The nursery school on the roof terrace is still in operation.

The Cité Radieuse has benefited from several protection measures. In addition to being labelled Remarkable Contemporary Architecture, it is part of the Series listed as World Heritage. The facades were listed in 1964, at Le Corbusier’s instigation.

Since 1986, the facades, the terraces and their fittings, the entire portico and the space beneath it have been classified.

Inside, the common areas are classified: the entrance hall, the circulation areas with their facilities (lifts excepted), apartment n°643, today reserved for visits by the city of Marseille Tourist Office.

Another private apartment, number 50, which belonged to Lilette Rippert, the first teacher at the rooftop nursery school, has been fully listed since 1995.

Since the inscription on the World Heritage List, a procedure has also been initiated for classifying the garden, now a public park belonging to the City of Marseille, and the refuse collection station.

All the facades have been restored since 2007, starting with the west facade. The roof terrace, the waterproofing, the chimney, and various other parts were restored between 2010-2011, followed by restoration of the boiler room and the solarium adjoining the gymnasium on the roof terrace.

The entrance overhang (“cap”) and the facades of the nursery school were restored in 2022. The refuse collection station, recently fully classified, is being restored.